Technology

On this page...

I think I was always a bit of a gadget freak, a technology ‘amateur’ (in the French sense). As a child one of my favourite toys was Meccano, and I spent many happy hours making things with it. I ended up with a sizeable collection of Meccano, in lovely wooden boxes built by my father, but I don’t know what happened to them. I suspect they were left behind in Mexico when my parents moved to Spain in the 1990s.

What interested me with Meccano was not necessarily the thing being built, but rather the opportunities to include things such as gears, motors and levers. There was nothing more satisfying than to get the clockwork motor to provide the requisite amount of torque and speed to achieve the ends required: winding up the hook of a crane, or powering a rudimentary tractor.

The school I went to was not very well-endowed with teachers, and I never had a teacher who could have given me a good grounding in mechanics or indeed in physics. I was basically on my own when it came to this sort of thing.

As a teenager one of my prized possessions was my Bell bulb amplifier, which I tinkered with and used for various things, including as a sound amp for my electric guitar. I spent hours playing with my grandfather’s reel-to-reel tape deck, experimenting with sounds, splicing tape, and running it backwards through the heads. My grandfather, a notable gadget man, bought one of the first cassette tape recorders, a Philips/Norelco, and I was fascinated by that. When I bombed badly on my A levels, I did consider doing a vocational course in electronics, and I remember attending a taster class given by a local radio repair shop. I’m not sure why I gave this up, but it could be due to a feeling that the mathematics might be beyond me, although I realise now that I need not have worried about that.

When I was at university I had a number of projects which involved processing raw data, and I made use of the bank of electronic calculators in the Bata Library. These seemed to me like the very acme of modernity: they had LED displays, and memory functions which could be used to good effect in simplifying calculations. For one of my Geography projects I had to use the processing power of a real computer, and that was my first contact with computers at such. The university did not have its own computer, but had a time-share on a big mainframe computer at the University of Ottawa. I had to enter all of my data on a punched paper tape, using a big teletype terminal. If I made a mistake, I had to run the tape through to the point where the mistake had been made, making a duplicate tape, and carrying on with the duplicate once the correction was made. It was a laborious process! Once the data was all correct and verified on a print-out, it was sent over a modem to Ottawa. A few days later I went back to collect the results. It was very gratifying to have the statistics all done for me by the computer, and resulting print-out felt like a great achievement!

My first computer

In June of 1982 I was invited by a Longman author, John Higgins, to visit him and to see his ‘microcomputer’ which he was very excited by. I don’t know what I was expecting, but possibly something that looked like a largish stereo system. I was a bit surprised then to be taken to a small table where John whisked a cloth off something which turned out to be a small calculator-like thing. It was my first encounter with a Sinclair ZX81, and I immediately knew that this was something I needed to know a lot more about.

The following weekend I went to WH Smith at Wood Green and came back with a box containing my ZX81. I can’t remember how much it cost, but I think it was about £70. I brought it home, looked at the manual, plugged a cable from the computer to the TV, powered it on and then twiddled the TV tuner. Suddenly: magic! A cursor blinking at the bottom of the screen! I immediately started working through the manual, which was an introduction to Basic, and in no time at all I realised that this tiny machine was not only totally under my control, but was also capable of doing all the things that that mainframe in faraway Ottawa had done. This was the most amazing tool I had ever encountered!

The ZX81 was fairly primitive in almost every way. It had a very flaky keyboard where the keys were basically printed switches between two membranes, and needed a firm push to register. It had 1k (yes, one kilobyte!) of RAM on board. Programs in Basic could be written, but then they needed to be saved to a cassette tape on an ordinary tape recorder if they were to be kept. The reliability of the taped version was very patchy: often a saved program refused to re-load, and all the work was lost. The version of Basic was very… basic! It was driven by Z80 processor, and the only graphics available were chunky full-character graphics (one of really cool things was the ability to poke values directly into screen memory!). Still, despite these limitations, I was amazed at what the machine could do. In no time at all I had written a program which saved a lot of time and heartache doing the simple but laborious calculations needed by a book publisher to determine profitability and pricing on new titles. I had colleagues who were soon asking whether they could come and use my computer. It spoiled the fun of our new publications committee meetings where the interest had centred on using a calculator to catch colleagues out on arithmetical mistakes. Now the calculations were always 100% reliable.

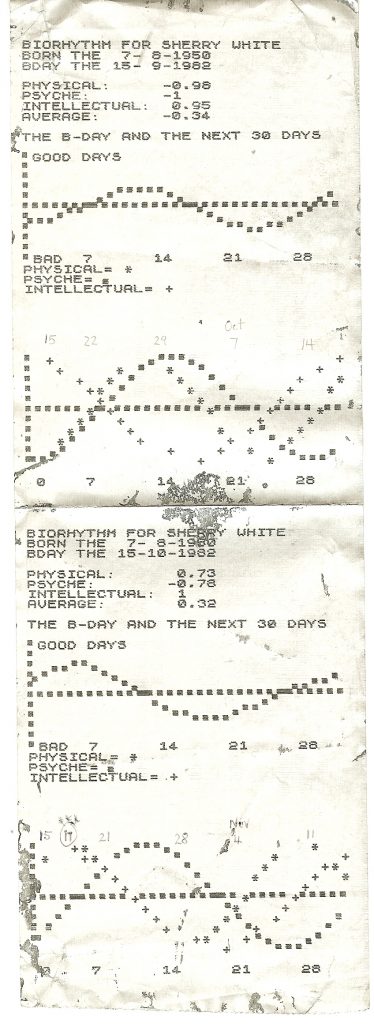

There were some peripherals available for the computer. My first purchase was a 16k RAM-pack, which felt dreadfully extravagant! Surely no-one would need as a much as 16k? The problem with the RAM-pack was that it clipped onto an edge connector on the back of the computer. Any sudden movement would cause the connection to fail, and all work would be lost as the computer went into re-set. My second purchase was a thermal printer which printed results and programs onto a strip of silver-coated paper about 3 inches wide. For a while this became a standard attachment to all pre-publication documents at work.I also managed to buy an add-on keyboard which made life much easier, although it was soon put into retirement when the BBC micro came along.

BBC Microcomputer

It was about this time that the BBC micro made an appearance. I was one of the early adopters, and it was with great pride that I found myself in possession of a machine which was infinitely more powerful and sophisticated than the Sinclair. Because it was so new, there was very little software available for it initially. Also, there were very few peripherals. Although floppy disk drives soon came on the scene, at first I was dependent on a cassette tape recorder for data and program storage. One of my first projects was to write a rather basic wordprocessing program. This worked as a stop-gap, but very soon there was some serious commercial software available, some of it on ROMs that could be inserted straight into the motherboard. One such ROM was the famous Wordwise wordprocessor, which I used for quite a long time. It was a powerful wordprocessor which supported escape sequences for printing effects, and it was certainly not WYSIWYG, but it meant that from that time onwards I wrote as little by hand as possible!

Before long I was able to buy one of the first disk drives for the BBC and that made a huge difference. It was possible at last to efficiently save and retrieve programs and data.

I was interested in the question of how computers might be used to help in language learning, and before long I found myself writing some programs in BBC basic which used text and word games. One of the innovative aspects of the programs I wrote was the separation of data used from the programs themselves. This meant that the programs could be used by teachers in a wide variety of situations, since all they needed to do was to use a very simple wordprocessing program (supplied with the package) to input data which was relevant to their students. The programs could then make use of this data to deliver language-based games. I offered the package as a publishing proposal to Longman, and this led to the publication of Quartext, a suite of four text-based programs {{reminisce:call_brochure.pdf|(Longman CALL brochure)}}. John Higgins, listed as my co-author, had developed the original idea of the main Quartext programme, which he called Storyboard, and which he wrote for the Sinclair Spectrum, and I felt it was only fair to acknowledge his contribution, although all the coding for the BBC micro and the independent text source was mine.[[reminisce:technology:bbc_basic| Click here to see a sample of the BBC Basic coding.]] I subsequently developed another suite called Quartext Plus, which was also published by Longman. In addition, I developed a number of word-based games which were published by Wida Software.

I soon found myself in the position which all developers of published software must inevitably face. As the technology developed, I needed to keep up with fixes, patches and new editions. The most troublesome for me was a major development of the BBC computer which allowed it to be used on school networks (a novel idea at the time). This meant adapting the software to run under the Network Filing System, which was itself subject to constant development, and it was a headache for me because I did not have a network at home, and could only test software in a school which had the system installed. I also wanted to speed up the programs and therefore embarked on a project of converting all of the BBC Basic source code into 6502 machine code. That was fun and satisfying, but I confess that it did take up a huge amount of my spare time, at the expense of my social life and family!

By the late 1980s my career had progressed and I had less and less time to devote to writing software. In addition, schools were beginning to move increasingly towards MS-DOS systems, and the writing was on the wall for the BBC micro computer as the preferred platform for education. I did oversee the translation of Quartext into an MS-DOS based format (programmed by a very competent French programmer in C+ if I remember correctly), but I never liked the graphics and also felt no ownership of this version, which is a pity, because it could have been made into quite a nice package with a bit of proper publishing care and attention.

PCs

By the early 1990s I was completely wedded to the use of MS-DOS based computers at work, and was no longer doing any coding at all. In 1987 the company bought a computer for my use which I was very pleased to have and which I continued to use right through until I completed my MBA in 1992. This was a Toshiba T3100e, and it was one of the very first ‘laptops’. It had a monochrome gas-plasma display, an Intel 80286 processor, a 20mb hard disk drive and a 3.5″ floppy drive. It booted to the DOS C:> prompt very quickly, and from that point software needed to be launched using DOS exe files. It was very heavy, and this kind of computer quickly came to be known as a ‘luggable’ rather than a true portable laptop. Nevertheless, it was magic and it was the first MS-DOS computer which I really enjoyed using.

Electronics

In the late 1980s and early 1990s I taught myself some basic electronics. This was partly because I wanted to add some interest to Lego installations, especially the Lego electric train set. I made up some basic circuits using LEDs for signals and IR receivers to do things like switch signals when a train passed. This could all be run using the BBC computer’s user port, which made it easy to interface to real-world applications. It was a little frustrating, though, because I didn’t have any sophisticated software to run on the BBC which would have helped to automate robotic tasks, and I didn’t at that stage have the time or patience to code everything up in Basic.